The Eurasian Pivot: Power, Connectivity, and Geopolitical Entropy in 2026

The Eurasian Pivot: Power, Connectivity, and Geopolitical Entropy in 2026

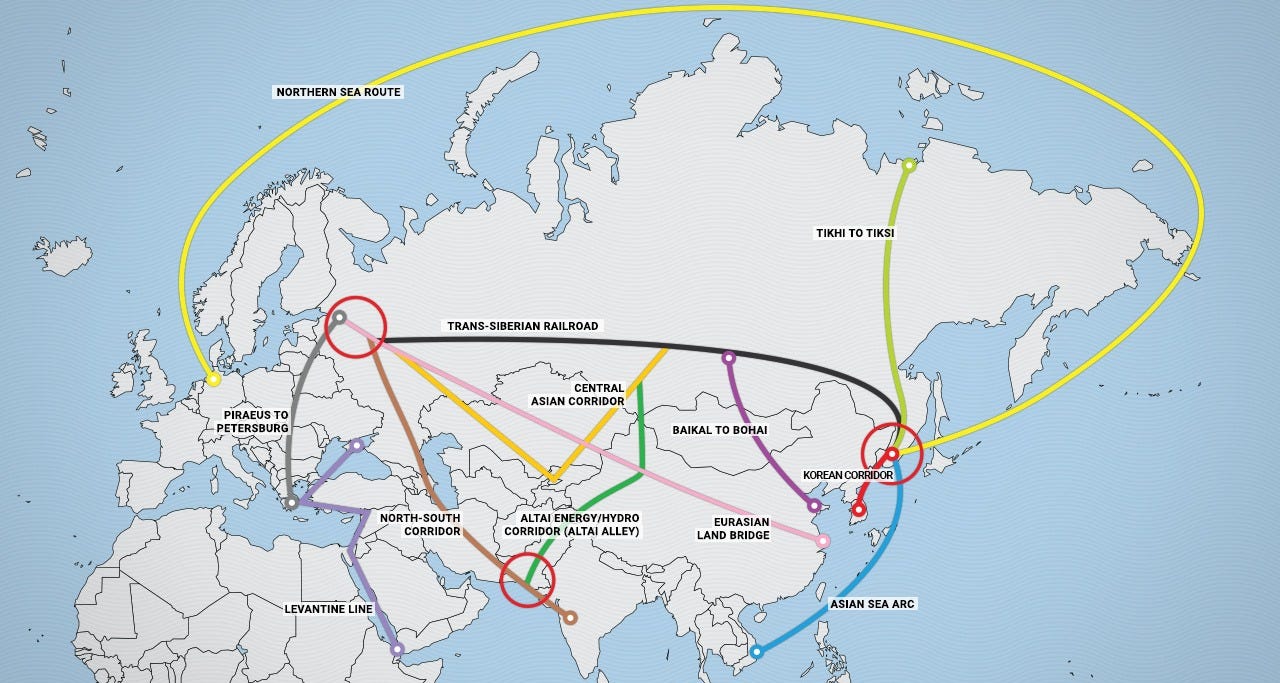

For over a century, the geopolitical destiny of the world has been theorized through the lens of the “Heartland.” Sir Halford Mackinder’s famous 1904 dictum—”Who rules the Heartland commands the World-Island; who rules the World-Island commands the world”—has never felt more relevant or more contested than it does in 2026. As we navigate this year, Eurasia is no longer a static landmass of post-Soviet nostalgia; it has become a churning laboratory of “geopolitical entropy,” where old alliances are decaying and new, high-speed corridors of power are being etched into the earth.

The current geopolitical landscape of Eurasia is defined by a violent decoupling from traditional Russian-centric infrastructure and a frantic race to establish “sovereign connectivity.” From the snow-capped mountains of Kyrgyzstan to the gas-rich shores of the Caspian Sea, the continent is undergoing a transformation that will dictate the global balance of power for the remainder of the century.

The Death of the Northern Corridor

For decades, the “Northern Corridor”—the vast network of railways and pipelines running through Russia—was the primary bridge between the industrial hubs of China and the consumer markets of Europe. It was the backbone of Eurasian integration. However, by early 2026, this corridor has reached a point of near-irreversible stagnation. The prolonged conflict in Ukraine and the subsequent tightening of Western “secondary sanctions” have turned the Trans-Siberian routes from economic lifelines into strategic liabilities.

Global logistics firms, once eager to shave days off sea-freight times by using Russian rails, have largely abandoned the route. This vacuum has accelerated the development of the “Middle Corridor,” or the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route (TITR). This route, which bypasses Russia by traversing Kazakhstan, the Caspian Sea, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkey, has seen a four-fold increase in cargo volume between 2022 and 2026. What was once a logistical pipe dream is now a multi-billion dollar reality, backed by the European Union’s “Global Gateway” initiative and a renewed “Turkic” alignment led by Ankara.

The Central Asian Scramble: From Buffer to Bridge

Central Asia is no longer just Russia’s “backyard” or a mere buffer zone. In 2026, the five “Stans”—Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan—have emerged as the new middle-ground of global diplomacy. This shift is characterized by “multi-vectorism,” a sophisticated diplomatic dance where these nations simultaneously court China for infrastructure, the EU for democratic legitimacy and technology, and the United States for security and investment.

Kazakhstan, in particular, has become the linchpin of this regional renaissance. As the world’s largest producer of uranium and a critical supplier of crude oil, Astana has leveraged its resources to ensure that no single Great Power can dominate its internal affairs. The 2026 Z5+1 meetings in Berlin and Tashkent have highlighted a new era of “Strategic Regional Partnership,” where Central Asian leaders are negotiating with the EU not as supplicants, but as critical providers of energy and mineral security.

However, this independence is constantly threatened by “Infrastructure Lawfare.” While the West offers sustainable development, China offers rapid, debt-financed construction through its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) 2.0. The competition over “Line D”—the contested natural gas pipeline from Turkmenistan to China—exemplifies this struggle. For the Central Asian states, the goal is to avoid being “debt-trapped” while ensuring they remain the essential bridge of the 2nm chip era.

The Moscow-Beijing Axis: A Marriage of Asymmetry

While Central Asia seeks independence, the relationship between Moscow and Beijing has entered a phase of “utilitarian integration.” By 2026, the “friendship without limits” has evolved into a clear hierarchy. Russia, isolated from Western financial systems, has increasingly become a junior partner in a Chinese-led Eurasian order.

The 2026-2030 SCO (Shanghai Cooperation Organization) Trade Action Plan, adopted under Russia’s chairmanship in Moscow, masks a deeper reality: the “sinicization” of the Russian economy. From the adoption of the Yuan in cross-border settlements to the dominance of Chinese automotive and tech brands in Russian cities, the border between the two giants is becoming economically porous.

For China, Russia provides a secure, land-based source of hydrocarbons and raw materials that are immune to a potential US naval blockade in the Malacca Strait. For Russia, China is the only remaining path to technological survival. Yet, this axis is not without friction. Beijing’s increasing footprint in Central Asia—traditionally Moscow’s sphere of influence—creates a quiet but persistent tension. The 2026 energy landscape is a “Gas Union” proposed by Gazprom versus the Chinese-led pipeline networks, a tug-of-war where the local states are the ultimate prize.

Energy Entropy and the Green Decoupling

Energy has always been the primary currency of Eurasian geopolitics, but 2026 marks a historic pivot. The European Union has formalized its total ban on Russian LNG and pipeline gas, forcing a radical re-engineering of the continent’s energy architecture. This “Green Decoupling” has turned the South Caucasus into the most critical chokepoint on the map.

Azerbaijan, through the expansion of the Southern Gas Corridor, has become Europe’s energy anchor. But the geopolitics of 2026 isn’t just about fossil fuels; it’s about the “Green Hydrogen” race. The Mangystau region in Kazakhstan is currently being developed into a global hub for carbon-free hydrogen, attracting billions in EU investment. This represents a shift from “extraction-based geopolitics” to “technology-based geopolitics.” The nations that control the renewable grids and the rare earth processing facilities will hold the leverage that oil sheiks held in the 1970s.

The South Caucasus: The Fragile Gateway

As the Middle Corridor matures, the South Caucasus has become a zone of intense strategic focus. Georgia’s role as a transit state for Western goods and Azerbaijani energy makes its internal political stability a matter of international security. Meanwhile, the relationship between Russia and Turkey in the Black Sea remains a complex game of “competitive cooperation.”

In 2026, Turkey positions itself as the “Eurasian Hub,” controlling the flow of grain, gas, and goods. Ankara’s influence through the Organization of Turkic States has created a cultural and economic “third way” that rivals both the Western liberal model and the Russo-Chinese authoritarian model. This “Neo-Ottoman” diplomacy is a crucial variable in the stability of the Middle Corridor, as Turkey balances its NATO obligations with its ambitions in the heart of Eurasia.

The Technology Frontier: Sovereign AI in the Heartland

A new layer has been added to Eurasian geopolitics in 2026: Digital Sovereignty. As mentioned in the “Silicon Shield” discourse, the race for AI and high-end compute has reached the steppe. Nations like Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan are investing heavily in “Sovereign AI” clusters to ensure that their digital infrastructure is not entirely dependent on either Silicon Valley or Shenzhen.

The struggle for data supremacy and fiber-optic connectivity is the 21st-century equivalent of the “Great Game.” The laying of subsea cables across the Caspian Sea and the integration of Central Asian data centers into the Global Gateway digital network are the new fortifications. In this era, a nation’s power is measured not just by the size of its tank divisions, but by its “compute-per-capita” and its ability to protect its domestic algorithms from foreign influence.

Conclusion: The Unfinished Map

As we look toward the horizon of 2027 and beyond, Eurasia remains a work in progress. The old Soviet borders are fading, replaced by a complex lattice of trade agreements, energy corridors, and digital firewalls. The continent is no longer a monolith; it is a collection of “poles” that are constantly shifting.

The “geopolitical entropy” of 2026—the breakdown of old systems and the chaotic emergence of new ones—suggests that the era of a single dominant Eurasian power is over. Instead, we are seeing the rise of a “Networked Eurasia,” where power is found in the nodes and the connections. Whether this leads to a new era of prosperity or a series of localized conflicts over resources and routes remains the defining question of our time.

One thing is certain: the road from Shanghai to Rotterdam no longer runs through a single gatekeeper. The Heartland has been decentralized, and in that decentralization lies both the greatest risk and the greatest opportunity for global stability.